Austerity? What austerity?

Along with all the news about the financial crisis in Greece there was a constant stream of snarking, especially from Paul Krugman, about how ‘austerity’ ruined the European economy. The same commentators applaud the European Central Bank plans for quantitative easing (QE).

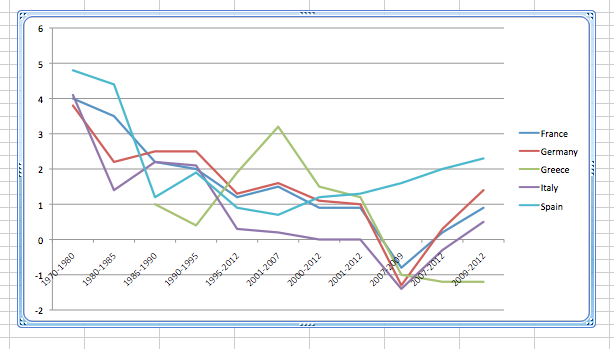

First, what austerity? When I look at the numbers I do not see a lot of austerity, and where austerity did occur, the economy improved. Look at the top four eurozone economies, and add Greece to the list to satisfy current interest. Here’s what I see:

In Germany, government spending increased. No austerity.

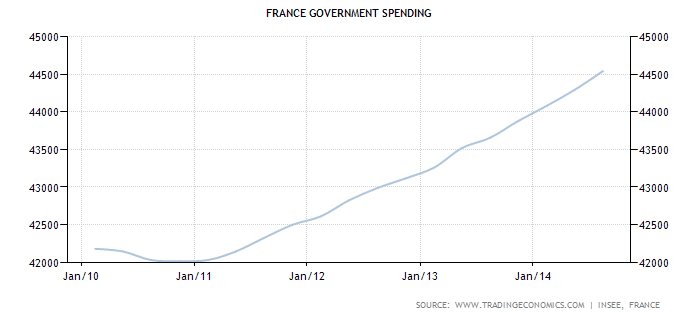

In France, ditto. Government spending is up, no austerity.

In Italy government spending is down, but their GDP is rising. No pain from austerity.

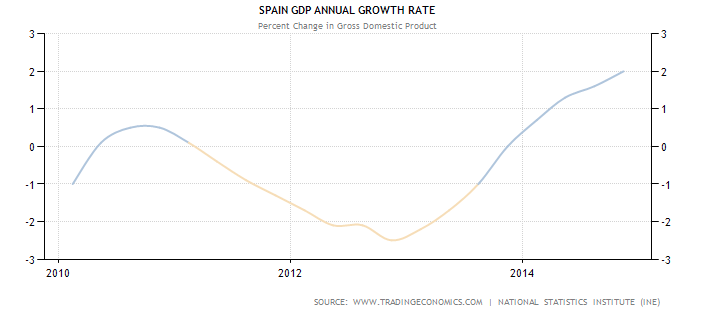

Same thing in Spain. Government spending is down, rising GDP.

In Greece, government spending dropped 2010 through early 2014, but then spiked upwards. Greek GDP bottomed in 2011 and has been climbing since then.

Why are reporters and columnists telling us that European governments implemented austerity, and that this hurt their economies? Are they not looking at the data?

Summarizing: whatever ‘austerity’ occurred was isolated and brief, and where austerity might have happened, economies grew.

Fiscal and monetary tools are inadequate

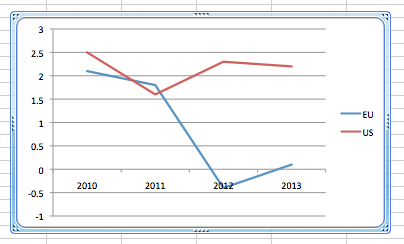

Yes, there is a problem with the EU economy. Angela Merkel said recently that Europe is 8% of world population, 25% of the world economy, but 50% of welfare spending. The following chart uses World Bank data to contrast GDP growth rates for the US and the EU.

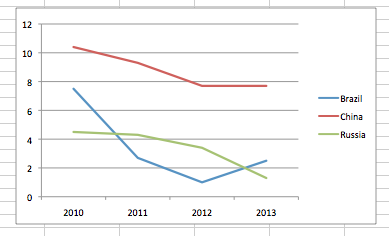

The EU tried a fiscal tool – austerity. That didn’t work. Now they’re trying a monetary tool – quantitative easing. That won’t work either. QE was not a big success in the US. Three of the world’s big emerging economies, Brazil, Russia, and China also tried QE. Starting in 2008 they started a stimulus program, bigger than what Obama tried in the US. It failed. See the following chart, using World Bank data.

Symptoms of a non-competitive economy

The problem is that Europe’s economy is not competitive. There are some very visible symptoms:

- Sluggish business start up rates, as cited by both OECD and think tank data.

- Low investment returns to venture capital firms, compared to the US.

- Poor success in creating big new companies: ‘According to an analysis of the world’s 500 biggest publicly listed firms by Nicolas Véron and Thomas Philippon of Bruegel, a think-tank, Europe gave birth to just 12 new big companies between 1950 and 2007. America produced 52 in the same period…Europe has only three big new listed firms founded between 1975 and 2007. Of those, two were started in Britain or Ireland, which are closer to America in their attitude to enterprise than continental Europe. Europe’s big privately held firms, too, mostly date from before 1950, often a very long time before.’

- Falling labor productivity. Labor productivity reflects how efficiency improvements and technological progress make labor inputs more productive. Economists cite labor productivity as a major factor in determining living standards. You want this number to go up; however, for the biggest EU economies and Greece, it is going down. See the following line chart, which uses OECD data.

- Unfriendly business climate. The World Bank has released a 2014 national ranking of the ease of doing business. The US ranks 7, Germany ranks 14, France 31, Spain 33, Italy 56, and Greece 61. If the four largest EU countries ALL rank out of the top ten in terms of business friendliness they have bigger fish to fry than fiscal and monetary tweaks.

The anecdotal evidence

A quick survey of news on the economic malaise in Europe turns up a lot of stories about the ways in which businesses find Europe a tough place to operate. The all-time classic is the story of the CEO of an American tire company, Titan International, responding to a French government plea to take over a Goodyear plant scheduled for closing:

How stupid do you think we are?…The French work force gets paid high wages but works only three hours. They have one hour for their breaks and lunch, talk for three and work for three. I told this to the French unions to their faces and they told me, ‘That’s the French way!’

Italy has five separate national police forces, with twice as many police per capita as Germany.

France has many companies with 49 employees, because when a business grows to 50 employees it requires creating three worker’s councils, a profit-sharing scheme, and consulting with other workers before anyone is fired.

Austrians are legally entitled to 38 days of annual leave.

In Estonia mothers get 18 months of maternity leave, with full pay from their employer.

An article in the Economist listed problems for eurozone entrepreneurs:

’many countries treat honest insolvent entrepreneurs more or less like fraudsters, though only a tiny fraction of bankruptcies involve any fraud at all. Some countries keep failed entrepreneurs in limbo for years. Britain will discharge a bankrupt from his debts after 12 months; in America it is usually quicker. In Germany people expect it to take six years to get a fresh start, according to the commission; in France they expect it to take nine … In Germany bankrupts can face a lifetime ban on senior executive positions at big companies.’

‘If young firms are to survive near-terminal mistakes, or fluctuating demand, they need to be able to reduce staff costs quickly and cheaply when necessary. That is far harder in many European countries than elsewhere.’

‘The cost of paying out large severance packages (six months of severance pay is typical even for very recent hires) can be a huge drain for a small company. “In San Francisco and in China, a communist country, I pay one to two months,” says a beleaguered French chief executive who does not want his name attached to such a sensitive subject. Big severance packages also make it much harder for start-ups to recruit the professional managers that can take them into the big league.’

‘European business founders find it difficult to wield the entrepreneur’s main weapons: the stock options and free shares that make start-ups attractive to employees. The legal complexity of giving new hires free shares is prohibitive…That further limits entrepreneurs’ ability to tempt people into a risky career move.’

The bottom line

Europe is not suffering from austerity. Indeed, where austerity was tried the economy grew. Monetary stimulus (QE) won’t help.

Europe needs to focus on returning to the kind of competitiveness that brought prosperity in the post-WW2 years.